What is autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD)?

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is a rare genetic condition that causes cysts (balloons of fluid) to develop in the kidneys and liver. The cysts are not cancerous and the fluid inside them is harmless.

As these cysts grow over the years, they ‘squish’ and damage the healthy kidney tissue and enlarge the kidneys. This makes it hard for the kidneys to filter the blood properly and can eventually result in kidney damage.

The cysts can be as small as a pea or as large as a grapefruit.

ADPKD affects around 1 in 2,000 people in the UK. It is equally common in men and women, although men tend to be more severely affected and are often diagnosed at a younger age than women.

What are the signs and symptoms of ADPKD?

Most people with ADPKD live completely normal lives with very mild or no symptoms for the majority of the time.

Cysts usually start to form in late childhood or early adulthood, although in rare cases they may not develop until a person is in their 60s or 70s. Most people with ADPKD have lots of cysts in their kidneys and liver by the time they reach old age. As the cysts grow, they cause the organs to enlarge. The larger they get, the more space they take up in the abdomen, causing it to become swollen.

Other common ADPKD symptoms include:

- high blood pressure

- urinary tract infections

- pain in the sides and/or back

- kidney stones

There may also be blood in the urine (haematuria). This happens when a tiny blood vessel in the wall of a cyst breaks, causing the cyst to bleed. This bleeding is usually not serious, but it is recommended that you see your doctor if you notice blood in your urine so the cause can be determined.

Occasionally, a kidney cyst can become infected, which can be very painful. This can sometimes happen after other infections and can cause sweating, shaking, fever and a high temperature.

What causes ADPKD?

The kidneys contain millions of tiny filtering units called nephrons. Each nephron is made up of a filter (glomerulus) which is connected to a tube (tubule). The nephrons filter the blood to return nutrients to the body and get rid of waste in the urine. In ADPKD, cysts develop as swellings along the tubule. These then multiply and grow until they stop the nephron from working. The healthy kidney tissue gets squished by the growing cysts. This eventually affects the kidneys’ ability to filter the blood properly, leading to kidney damage.

An ADPKD kidney in comparison to a normal kidney; Photo courtesy of the PKD Foundation

How is ADPKD diagnosed?

ADPKD is usually diagnosed in adulthood by genetic testing or by an ultrasound scan. An ultrasound scan uses soundwaves to create an image of the inside of the body and is used to identify cysts and enlarged kidneys.

Blood and urine tests are also used to monitor kidney function.

Does ADPKD affect other parts of the body?

As well as the kidneys, cysts can also develop in the liver and pancreas. Liver cysts tend to be larger in women than in men. The cysts can be uncomfortable if they grow very large, but they very rarely cause liver damage.

One in 10 people with ADPKD have cysts in their pancreas, but these almost never cause problems.

One in 20 people with ADPKD have cysts inside the skull, which can cause an aneurysm. This is more common in people who smoke and/or have high blood pressure.

Does ADPKD run in families?

ADPKD is a genetic condition. It is caused by an abnormality or mutation in one of two genes, PKD1 or PKD2. Most people get ADPKD when they inherit a faulty copy of one of these genes from a parent.

In some cases, however, a genetic change occurs spontaneously. This can cause ADPKD to develop in someone whose parents do not have the mutated gene. This new mutation can then be passed onto the next generation.

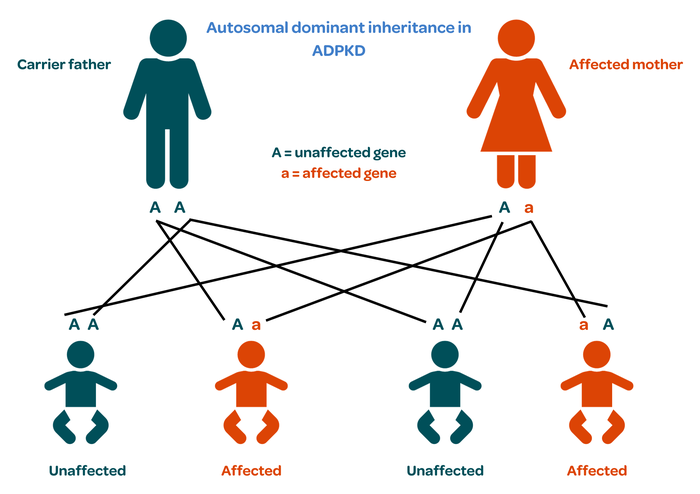

ADPKD is inherited from one generation to the next in a pattern known as autosomal dominant inheritance.

Everybody has two copies of the PKD genes, one from each parent.

One copy of the faulty gene is enough to cause the condition.

There is therefore a one in two chance that a child born to an affected person will receive the abnormal gene and eventually develop ADPKD themselves.

How is ADPKD treated?

There is currently no cure for ADPKD so treatment focuses on maintaining a good level of health to protect the kidneys. This includes:

- Avoid smoking. Smoking damages the blood vessels in the kidneys and speeds up kidney damage.

- Control blood pressure. High blood pressure damages the kidneys and increases the risk of stroke and heart disease. Blood pressure should therefore be checked regularly. This can be done at home with a blood pressure machine from a chemist.

- Eat a balanced diet. It is especially important to limit the amount of salt in the diet as too much salt can cause high blood pressure.

- Exercise regularly. This will help to control blood pressure. Contact sports such as boxing or rugby should be avoided, however, especially if large cysts have been identified on a scan, due to the risk of them bursting, bleeding and causing infections.

- Drink enough fluid. There is currently no evidence that drinking excess amounts of fluid slows the growth of cysts. It is therefore recommended that people with ADPKD drink enough so they are not thirsty, but not too much. Six to eight 200ml glasses of water a day is usually sufficient in the UK, but this may need to be increased if more fluid is lost through heavy exercise, sweating or diarrhoea.

- Avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These are a type of medication used to relieve pain, reduce inflammation and bring down a high temperature. They include ibuprofen and diclofenac. NSAIDs can cause scarring in the kidneys so it is best for people with ADPKD to avoid them, and ask their doctor or pharmacist to suggest safer alternatives.

A tablet called tolvaptan may be prescribed to slow the growth of the cysts if your kidney function is getting worse quickly. Genetic testing or more detailed scans are sometimes used to see if tolvaptan will be a suitable treatment.

Large cysts may need to be drained during an operation, although this is rare as it can just give another cyst more room to grow.

People with ADPKD will usually be seen once a year by a kidney specialist to monitor their general health and kidney function. More frequent monitoring will be needed if blood tests show signs of kidney damage.

Half of people with ADPKD will develop kidney failure by the age of 60 and will need dialysis or a kidney transplant. However, with the right treatments most people with ADPKD remain in good health for decades.

Where can I get more information or support about ADPKD?

Read more about Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease on the NHS website.

For more information on ADPKD including its diagnosis, symptoms and treatment, visit the PKD Charity.

Publication date: 11/2023

Review date: 11/2026

This resource was produced according to PIF TICK standards. PIF TICK is the UK’s only assessed quality mark for print and online health and care information. Kidney Care UK is PIF TICK accredited.