What is hyperoxaluria?

Hyperoxaluria (also known as primary hyperoxaluria (PH) or oxalosis) is a group of rare genetic conditions that occur due to a build-up of a salt-like substance called oxalate. This can cause kidney stones to develop and can eventually lead to kidney failure.

Hyper – too much

Oxal – oxalate

Uria – in the urine

Hyperoxaluria affects around 1 in 500,000 people in the UK.

Three different types of hyperoxaluria have currently been identified, known as types 1, 2 and 3. Each type is caused by a different genetic mutation.

- Type 1 is the most common form and affects 8 out of 10 people with hyperoxaluria.

- Types 2 and 3 each affect 1 in 10 people with hyperoxaluria.

Hyperoxaluria is a different condition to secondary hyperoxaluria, which occurs alongside other conditions such as Crohn’s disease or pancreatitis.

What are the signs and symptoms of hyperoxaluria?

Some people with hyperoxaluria do not have any symptoms, whereas others will have lots of kidney stones. This variation can even be seen within the same family (hyperoxaluria is a genetic condition and it can run in families, as explained below).

The most common symptoms of hyperoxaluria are related to kidney stones, which most people with hyperoxaluria develop before the age of 20. Symptoms include:

- pain in the lower back or groin (renal colic) which can come and go in waves and range from mild to severe

- fever

- chills and shakes

- frequent bed wetting in children

- urinary tract infections

- blood in the urine (haematuria).

Other symptoms of hyperoxaluria include:

- reduced or delayed growth

- increased risk of bone fractures

- anaemia.

What causes hyperoxaluria?

Hyperoxaluria occurs due to a build-up of a salt-like substance called oxalate. Oxalate is found in foods such as almonds, spinach and rhubarb and is also produced in the body. It is normally absorbed by the small intestine and leaves the body in the urine.

However, in hyperoxaluria, the enzymes that control the production of oxalate are faulty, which causes too much oxalate to be produced. The excess oxalate combines with calcium to form crystals, which can eventually turn into stones. These can block the tubes of the kidney and can eventually lead to kidney failure.

How is hyperoxaluria diagnosed?

Hyperoxaluria is usually diagnosed in older children and adults by genetic testing. In rare cases, it can develop in babies when it is often more severe.

Blood and urine tests are used to measure oxalate levels and check for kidney damage.

Kidney stones can be seen on ultrasound scans. An analysis of a stone that has been passed from the body will show that is made up of calcium oxalate.

Does hyperoxaluria affect other parts of the body?

When hyperoxaluria damages the kidneys, oxalate also starts to build up in other parts of the body, including the bones, skin, liver and heart. This is known as systemic oxalosis.

Further symptoms can then include:

- bone pain and frequent fractures

- skin rash or mottling

- enlargement of the liver and/or spleen

- irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias).

Does hyperoxaluria run in families?

Hyperoxaluria is a genetic condition so it can run in families. A child may have hyperoxaluria even if their parents do not have any symptoms of the condition themselves.

The three types of hyperoxaluria are caused by mutations in different genes:

| Hyperoxaluria type | Gene affected |

|---|---|

| Type 1 | AGXT |

| Type 2 | GRHPR |

| Type 3 | HOGA1 |

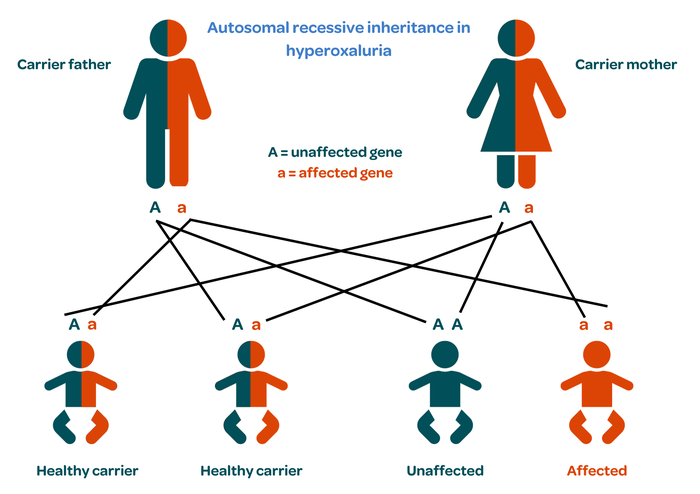

Everybody has two copies of these genes, one from each parent.

Healthy people have two normal copies.

Carriers have one copy that works normally and one that doesn’t. Carriers are usually healthy because the normal copy can still do its job. However, they can still pass hyperoxaluria on to their child.

In people with hyperoxaluria, neither copy of the gene works properly.

When both parents are carriers, a child could be healthy with two normal genes; a healthy carrier like their parents, with one healthy and one faulty gene; or affected, with both genes being faulty. This pattern is called autosomal recessive inheritance.

Genetic counselling may be offered depending on family history.

How is hyperoxaluria treated?

A new medication called lumasiran has recently been approved to treat hyperoxaluria type 1. Lumasiran reduces the levels of oxalate in the urine, preventing kidney stones from forming.

Vitamin B6 may also be prescribed for people with hyperoxaluria type 1, although not everyone responds well to this.

People with all types of hyperoxaluria are advised to drink lots of liquid (at least three litres a day). This helps to increase the amount of urine that is produced so that the body can get rid of more oxalate and stop it from building up to form kidney stones.

Dietary changes may be recommended to avoid foods that high in oxalate. This should only be undertaken with advice and monitoring by a specialist kidney dietitian.

Small kidney stones can be passed in the urine with little or no pain and may just require monitoring with ultrasound scans to check their location. However, large stones may require surgery, especially if they are at risk of causing blockages in the kidney and leading to long-term damage.

There are various ways in which stones can be removed.

- Lithotripsy – uses sound waves to break the stones into smaller pieces that can then be passed in the urine.

- Endoscopy – involves passing a flexible fibre optic ‘telescope’ called an endoscope up the bladder and ureters to see the stone directly. Special tools built into the endoscope are used to capture or break up the stone so it can be removed more easily.

- Open surgery – to remove stones is rarely needed.

Kidney function can decline very quickly, especially in children. If kidney failure develops, dialysis and/or a transplant may be needed. Haemodialysis (HD) is usually recommended as it is more effective at removing oxalate than peritoneal dialysis (PD).

Dialysis is often needed more frequently than for other causes of kidney failure (6 or 7 times a week compared with the usual 3 or 4) in order to keep oxalate levels low.

People with hyperoxaluria type 1 may be offered a combined liver and kidney transplant as the new liver can replace the damaged enzymes and stop hyperoxaluria from reoccurring in the new kidney.

Where can I get more information or support about hyperoxaluria?

For more information on hyperoxaluria, including its genetics, diagnosis, symptoms and treatment, visit the European Primary Hyperoxaluria Patient Advocacy Group.

Publication date: 11/2023

Review date: 11/2026

This resource was produced according to PIF TICK standards. PIF TICK is the UK’s only assessed quality mark for print and online health and care information. Kidney Care UK is PIF TICK accredited.