What is autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD)?

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) is a rare, severe, genetic condition that causes cysts (balloons of fluid) to develop in the kidneys and liver. The cysts are not cancerous and the fluid inside them is harmless.

As these cysts grow, they damage and enlarge the kidneys by ‘squishing’ the healthy kidney tissue. This makes it hard for the kidneys to filter the blood properly and can eventually result in kidney damage.

The cysts can be as small as a pea or as large as a grapefruit.

ARPKD affects around 1 in 20,000 people in the UK and is equally common in men and women.

ARPKD is a very severe disease. About one in three babies with confirmed ARPKD die of breathing problems within the first four weeks because their lungs do not develop properly in the womb.

However, nine in 10 children who survive their first month are alive by age five and most survive into adulthood. Research is taking place into possible future treatments to ensure the best chance of survival for those with ARPKD.

What are the signs and symptoms of ARPKD?

In general, the earlier the first signs of ARPKD develop, the more severe the condition.

ARPKD can be diagnosed before birth during an ultrasound scan of the mother. The baby’s kidneys may be enlarged or show as abnormally bright on the scan.

In newborn babies, the kidneys may be so large that the tummy appears swollen. An ultrasound scan may show cysts in the kidneys and blood tests may show that kidney function is reduced.

Most people with ARPKD develop kidney and/or liver problems during childhood. The speed at which ARPKD leads to kidney failure is different for each child. Some will only have a loss in organ function at first, whereas others will have complete failure or either or both organs at a young age. Children with ARPKD need careful monitoring from specialist treatment teams.

Other common symptoms in ARPKD in children include:

- excess thirst, preferring water to food

- reduced growth due to poor nutrition

- bed-wetting due to increased production of urine

- high blood pressure

- urinary tract infections (more common in girls than boys)

- pain in the stomach or back

What causes ARPKD?

ARPKD is a caused by a genetic mutation that results in the faulty development of the small tubes (tubules) of the kidneys and the bile ducts in the liver. Swellings and cysts develop in both organs, affecting their ability to function properly. Scarring (fibrosis) can also occur, which can lead to further organ damage.

How is ARPKD diagnosed?

ARPKD is usually diagnosed in babies and young children. In some cases, it is diagnosed during the mother’s pregnancy by an ultrasound scan. This uses soundwaves to create an image of the inside of the body and is used to identify cysts and enlarged kidneys.

When ARPKD is diagnosed before birth, the mother will have more frequent scans to check on the baby’s size and health, as well as the amount of amniotic fluid in the womb. The birth may need to take place in a specialist centre to ensure appropriate support for the baby.

Blood and urine tests are also used to monitor how well the kidneys are working.

ARPKD may also be confirmed by genetic testing, which is becoming more reliable with improvements in genetic techniques. This is usually only offered when the parents have already had another child with ARPKD.

Does ARPKD affect other parts of the body?

ARPKD can cause breathing difficulties as the baby’s lungs may not have developed properly in the womb due to a lack of amniotic fluid. Enlarged kidneys can also press on the lungs and make it difficult to breathe.

The large kidneys can push other organs out of the way, leaving little room for food in the stomach. Babies may require ‘artificial feeding’ through a small tube that is passed through the nose and down into the stomach.

Cysts can also develop in the liver and cause infections, which may need to be treated by antibiotics. ARPKD can also cause varicose veins to develop in the stomach. These may need treatment with a procedure called an endoscopy where a flexible ‘telescope’ (endoscope) is passed down the throat into the stomach.

Does ARPKD run in families?

ARPKD is a genetic condition. It is caused by an abnormality or mutation in a gene called PKHD1.

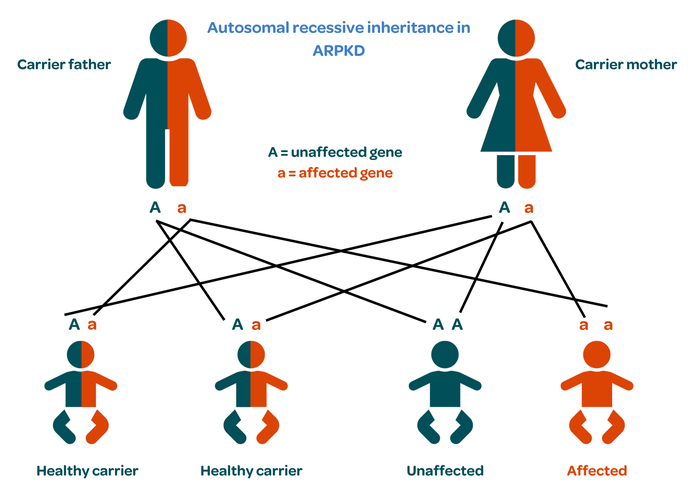

Everybody has two copies of the PKHD1 gene, one from each parent.

Healthy people have two normal copies.

Carriers have one copy that works normally and one that doesn’t. Carriers are usually healthy because the normal copy can still do its job. However, they can still pass ARPKD on to their child.

In people with ARPKD, neither copy of the gene works properly.

When both parents are carriers, a child could be healthy with two normal genes; a healthy carrier like their parents, with one healthy and one faulty gene; or affected with both genes being faulty. This pattern is called autosomal recessive inheritance.

If ARPKD is confirmed early in a pregnancy, antenatal counselling may be offered to discuss options about the future of the pregnancy.

If both parents have been confirmed as carriers of ARPKD, pre-natal and/or pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) may be offered. This involves testing embryos for ARPKD during a cycle of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and only transferring unaffected embryos to the mother’s womb to ensure the birth of a child without ARPKD.

How is ARPKD treated?

There are currently no treatments that can cure or slow the progression of ARPKD. Treatment therefore aims to manage the symptoms and should be led by a specialist team with expertise in ARPKD.

A newborn baby with breathing difficulties may need treatment in a paediatric intensive care unit and be placed on a ventilator to help them to breathe.

Young children with ARPKD have an increased risk of dehydration if they get a fever or diarrhoea. It is therefore very important that they drink enough water, especially during hot weather and exercise.

Regular blood and urine tests are needed to monitor kidney function. Mild kidney problems may be able to be treated by diet adjustments and blood pressure medication.

In some cases, the child’s kidneys are so large that one or both of them need to be surgically removed to make space in the abdomen for them to feed.

About six in 10 children with ARPKD will have developed kidney failure by the age of 10 and need dialysis or a kidney transplant.

One in 10 children will need a liver transplant or a joint liver and kidney transplant.

ARPKD does not reoccur after transplant and children can usually live a normal, active life.

Where can I get more information or support about ARPKD?

For more information on ARPKD including its diagnosis, symptoms and treatment, visit the PKD Charity.

Publication date: 11/2023

Review date: 11/2026

This resource was produced according to PIF TICK standards. PIF TICK is the UK’s only assessed quality mark for print and online health and care information. Kidney Care UK is PIF TICK accredited.