1. The man who developed the fundamentals of dialysis used a secret lab to hide his experiments.

Thomas Graham was Scottish chemist in the mid-1800s. Born in Glasgow, Graham was meant to enter the church, but after being encouraged into the sciences at Glasgow University he set up a secret lab while pretending to study theology. His father found out and destroyed the lab, but Graham continued his scientific work. Graham’s observations about the effects dialysis had on urine still influences treatments to this day.

2. The first dialyser (artificial kidney) was created using sausage skins, a washing machine, and orange juice cans.

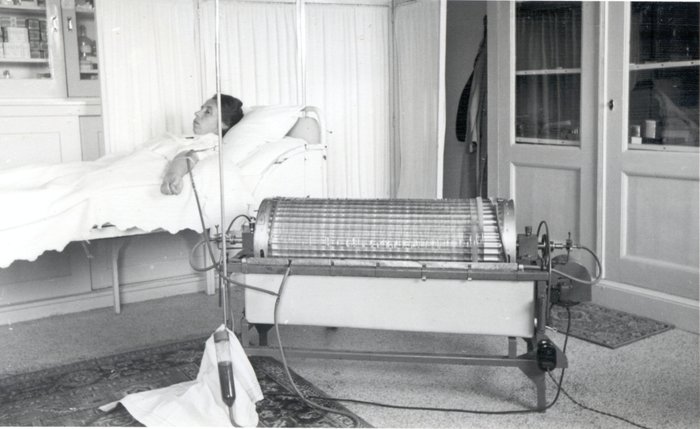

Dr Willem Kolff, the ‘father of dialysis’, was a Dutch physician who constructed the first dialyser in 1943. Because materials were so scarce during World War II, Kolff had to improvise and this resulted in the first dialyser being made from sausage skins, orange juice cans, and old washing machine parts.

3. The first successful dialysis treatment was carried out in 1945 on a 67-year-old woman who had been released from prison.

After the creation of the first dialyser, Dr Kolff treated 16 patients with acute kidney injury but had little success. Then, in 1945, one of his patients came round from a uremic coma after 11 hours of haemodialysis. In an interview, Kolff claimed that many people would not have been sorry if the patient had died, given she was a Nazi sympathiser, but he believed it was his duty as a physician to help her.

4. Dr Kolff hid around 800 people from the Nazis during World War II, all while trying to treat patients with kidney failure.

World War II broke out around the same time that Kolff began his research. Once the Nazis had occupied the Netherlands, Kolff was sent to work in a remote Dutch hospital. During this time, Dr Kolff worked with the Dutch resistance and helped hide around 800 people by diverting them from the transport trains into his hospital. He did all this while continuing his research and making artificial kidneys. After the war ended, Kolff donated the artificial kidneys he’d created to hospitals across the globe.

5. The first arteriovenous shunt was made of glass.

Nils Alwall is considered to be the second pioneer of dialysis. Born in Sweden, Alwall developed the first shunt in 1948. Until this invention, every time a patient was dialysed it required new needle and a new vein. Alwall’s shunt allowed up to seven dialyses to be performed on an animal, though it wasn’t as safe for humans due to the high risk of clotting and infection.

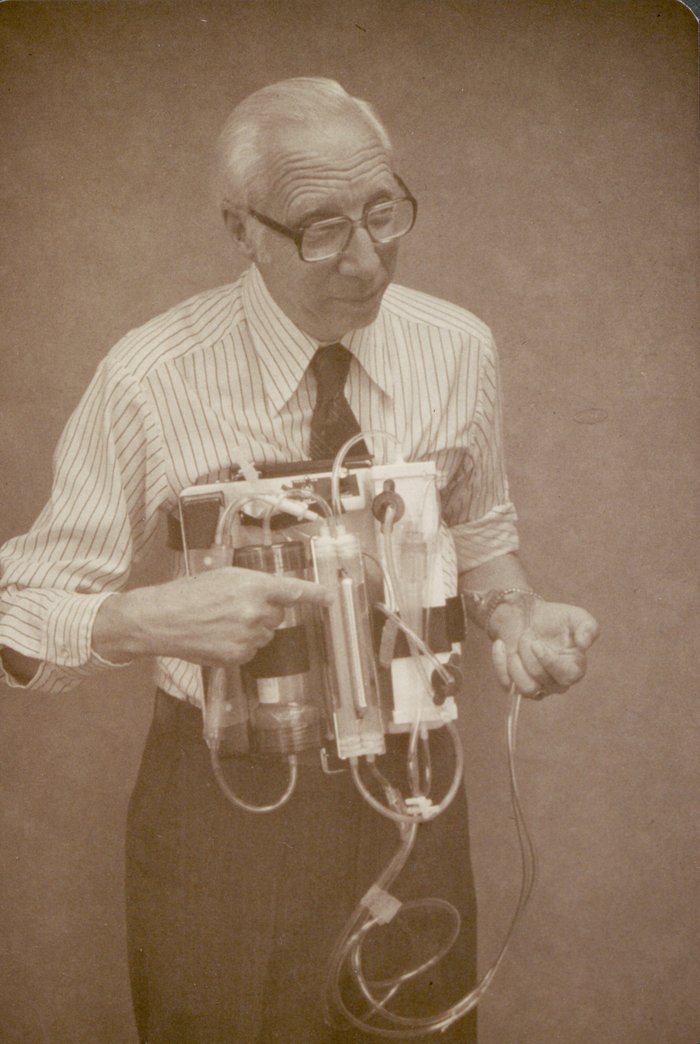

In the 1950s and 60s, using Alwall’s research, Dr Belding Scribner developed the “Scribner Shunt” which was made from Teflon. While the shunts are no longer used today (having been replaced by fistulas), they were vital in making long-term dialysis viable. Scribner went on to develop a portable dialysis machine which helped people to dialyse in their own homes.

6. The first attempt at an arteriovenous fistula failed because the patient had been prepared too diligently by their kidney team.

Throughout the 1960s, Dr James Cimino, an American physician, began to develop a way to connect an artery in the arm with a vein with a surgical procedure. This technique was dubbed the arteriovenous fistula.

There were issues with the first patient they tested on. They had based the fistula on an older technique which required the patient to be overhydrated. Cimino and his team ended up overcompensating and removing too much fluid which resulted in the patient’s blood pressure being too low. After a series of adjustments, the procedure went ahead as expected. The arteriovenous fistula remains the main access choice for dialysis patients to this day.

7. Gordon Murray, the third early pioneer of dialysis, had one of his designs for a dialysis machine stolen.

Murray was born in Canada and is best known for his work in cardiovascular surgery. In the early 1950s, Murray and his colleague Dr Roschlau had invented the “Murray-Roschlau artificial kidney”. However, before they could announce their results, one of the engineers on the team stole the designs and began to sell a similar dialysis machine in Germany. As neither Murray nor Roschlau had a patent for their machine, there was nothing they could do about it.

8. The first successful peritoneal dialysis may have come before the first successful haemodialysis.

There are few accounts of peritoneal dialysis being undertaken before the 1940s, but experiments documenting the infusion and removal of saline solution into and out of the peritoneal cavity of a guinea pig took place in 1923.

9. The first patient in the world to be treated by repeated haemodialysis lived for eleven years.

Clyde Shields was the first person with chronic kidney disease to be treated with long-term dialysis. His first session was in Seattle, USA, in March 1960 and Dr Scribner implanted the shunt. The success of Shields’ treatment led to the world’s first haemodialysis programme.

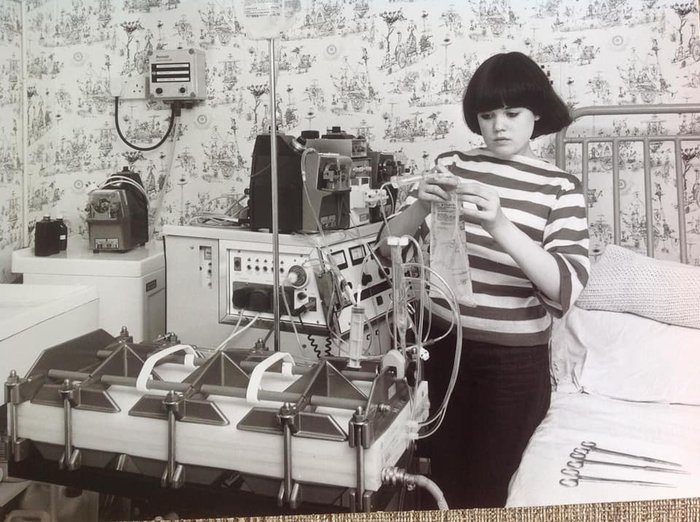

10. Modern dialysis barely resembles the older treatments.

Whether it is vascular access, infection control, or the machine itself, modern dialysis is wildly different to the treatments of the past. Kolff, Alwall, Murray, Scribner, and Cimino were pioneering in their development of dialysis, and as research into kidney disease continues, dialysis will only keep improving.

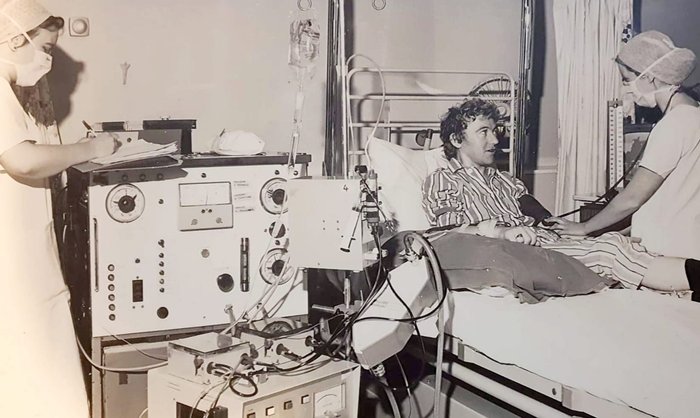

Dialysis in the 1970s and 1990s

Members of the Kidney Care UK community have shared photographs of the dialysis machines from their past.

Do you have any photographs of your dialysis sessions you'd like to share? We'd love to see them!

Dr Kolff and dialysis machine images reproduced with permission from Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah.